Brexit: bringing home the bacon

While ‘political Brexit’ was completed at the end of January with the UK’s departure from the European Union, ‘economic Brexit’ is still to come at the end of the year. The UK Government has made it clear that the UK will be leaving both the Customs Union and the Single Market on 31 December 2020 which will lead to a need for customs declarations and some physical checks on goods traded between the UK and the EU. In addition the EU/UK trade negotiations have stalled, which could lead to the imposition of tariffs by both sides on each other’s exports. This article considers what this means for UK imports, taking as an example imports of bacon - which forms part of the traditional British diet as a key ingredient in the full English breakfast and the bacon sandwich

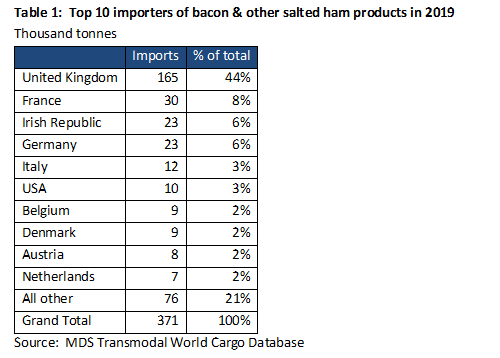

The UK imported 165,000 tonnes of bacon and other salted ham products in 2019, more than any other country in the world (Table 1). While the UK represents less than 1% of the world’s population, its demand for bacon and other salted ham products such as Italian prosciutto represents 44% of global imports and means that the average British person consumes 2.5 kilogrammes of these imported products each year.

Almost all the imports to the UK are from the EU, with 82% of imports from the Netherlands and Denmark alone (Table 2). Given the nature of the products, they are likely to be transported on a just-in-time basis in temperature-controlled conditions.

In February 2020 the UK Government announced that checks on EU importsto the UK from the EU would be subject to full customs and other controls – including customs declarations and sanitary checks on food products - from 1 January 2021. In addition, in the event that the UK fails to secure a trade deal with the EU by the end of year, some goods (including imported bacon) would be subject to the new UK Global Tariff. However, the UK Government has now announced that these controls will be phased in next year to give firms "time to adjust” due to the impact of Covid-19 in the following ways:

- Companies will be able to defer completing customs declarations and tariff payments for six months and some physical checks will be delayed to July.

- From 1 April 2021 companies importing products of animal origin, including meat, will have to pre-notify officials and provide the relevant health paperwork;

- By 1 July, all goods will be liable for any tariffs and customs declarations as well as full "safety and security" declarations. From this moment, there will be an increase in physical checks on livestock, plants and other sanitary and phytosanitary products at ports and other entry points.

This gives the impression that the

UK has given itself a six month breathing space to develop the required

infrastructure at ports or at inland clearance sites to avoid queues forming at

entry points such as the Port of Dover and the Eurotunnel terminal at Folkestone. However, the EU has said that it will implement

full checks on UK exports at the start of 2021 in order to control the EU’s

customs border with a 3rd country.

In the event that the EU’s new controls lead to delays in Calais, the UK

will find that the ferries are unable to discharge and re-load HGVs in Calais

and queues of trucks will form in both Kent and the Calais area. This means the UK has to rely on the

efficiency of the EU’s customs and border inspection procedures, which could

lead to disruption of supply chains and additional costs for imports of food

products such as bacon.

Even if there are no shortages of bacon on the supermarket shelves as the logistics providers seek to adapt to the post-Brexit regulatory environment, the price of a full English breakfast could well rise as additional transport costs and potential tariffs start to affect the cost of meat imports.