Changing lanes: consortia block exemption — extension or expiration?

- By Antonella Teodoro

- •

- 05 Mar, 2020

The imminent end of the period of extension has led to a great deal of debate as to whether the Consortia Block Exemption Regulation should be further extended — and, if so, for how long

Carriers say the CBER should be extended, pointing towards falling costs, rates and emissions facilitated through exploiting economies of scale made possible by the clustering into alliances

CONSOLIDATION HAS BEEN RAPID: IN 2019, THE THREE MAJOR PLAYERS CONTROLLED CIRCA 85% OF GLOBAL CAPACITY

THE European Commission decided in September 2009 to renew the Consortia Block Exemption Regulation to April 2015; it subsequently gave a further five years’ extension as part of the process that ended what was known as the former liner conference system (Council Regulation 4056/86).

The imminent end of the period of extension has led to debate over whether the CBER should be further extended — and, if so, for how long.

The argument against has been led by the International Transport Forum/Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development amid support by a number of trade associations, who say the high market shares enjoyed by a much-consolidated liner shipping industry should encourage regulators not to agree on an extension.

Meanwhile, the carriers say the CBER should be extended, pointing towards falling costs, rates and emissions facilitated through exploiting economies of scale made possible by the clustering into alliances.

In a draft regulation paper published last November (staff working document), the commission proposed extending the EU CBER, set to expire on April 25, 2020, for another four years without changing its current form.

This preliminary view has been based on an evaluation process put in place to determine whether: “In view of the general policy of harmonising competition rules and considering the major developments in the liner shipping industry in recent years, the CBER is still relevant developments in the liner shipping industry in recent years, the CBER is still relevant and delivering on its objectives, and whether it is doing so in a coherent, effective and efficient manner, creating EU added value.”

The evaluation was based on the following criteria:

• Effectiveness: considering the major developments in the industry, does the CBER still facilitate economically efficient co-operation that also benefits consumers?

• Efficiency: what is the effect of it on costs? Does it help undertakings to cut costs or conversely does it increase compliance costs? Which policy option would cause less burden or complexity?

• Relevance: is it still relevant considering the major developments in the industry and the modes of co-operation between carriers?

• Coherence: is it coherent with the general policy of harmonising competition rules and replacing sector-specific rules with measures (BERs or guidelines) providing general guidance on the application of Article 101 TFEU?

• EU added value: what is the added value of the CBER considering the commission’s measures of providing general guidance on the application of Article 101 TFEU?

The commission concluded that “the evidence basis of this evaluation is, to a large extent, made of input of stakeholders”.

It

added: “There is no reason to depart from the longstanding view that consortia

are an efficient way for providing and improving liner shipping services that

also benefits customers.

“A fair share of the benefits resulting from the efficiencies is passed on to

transport users. The CBER remains relevant as its objective to facilitate

consortia remains appropriate in view of the ensuing benefits for

customers.”

The news was welcomed by shipping lines represented by the World Shipping Council, whereas shippers and other key players in the industry have communicated their resentment, claiming that the CBER in its current form distorts competition and does not address poor service levels.

These positions were expressed during the public consultation to industry stakeholders (including shipper, port and forwarder trade associations) launched by the European Union, which closed on January 3. They drew attention to the dangers of further vertical integration, the need for legal clarity and lack of transparency with respect to the data used for evaluation.

Assessing long-term risk

Consolidation in the industry has been rapid. In 2006, the seven leading lines or the alliances of that time controlled 72% of global deepsea capacity. None had a share above 20%.

In 2019, the three major players controlled circa 85% of the global capacity deployed in the deepsea markets.

Acquisitions in the feeder market have reinforced this pattern. In 2006, measured by deployed capacity, the four leading North European carriers were independent. Today, the leading four are owned by deepsea lines or stevedores.

Meanwhile, the lines are extending their ownership in stevedoring and forwarding, which, it can be said, the CBER has helped establish conditions for extensive vertical integration.

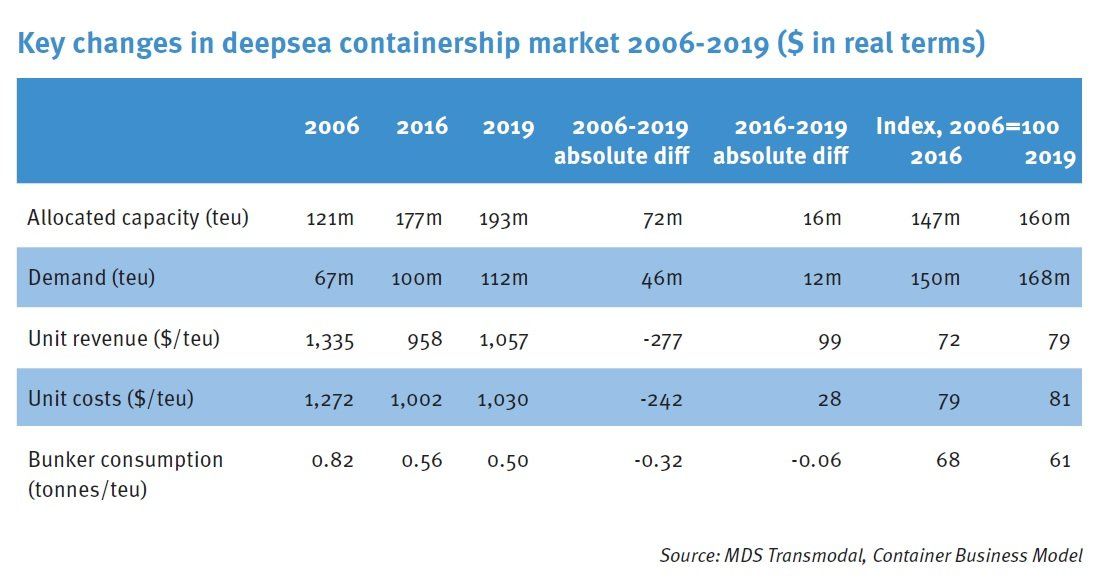

MDS Transmodal has developed a model that allocates estimated container flows to the services they are carried by the lines and estimates their operating costs and revenues (see table).

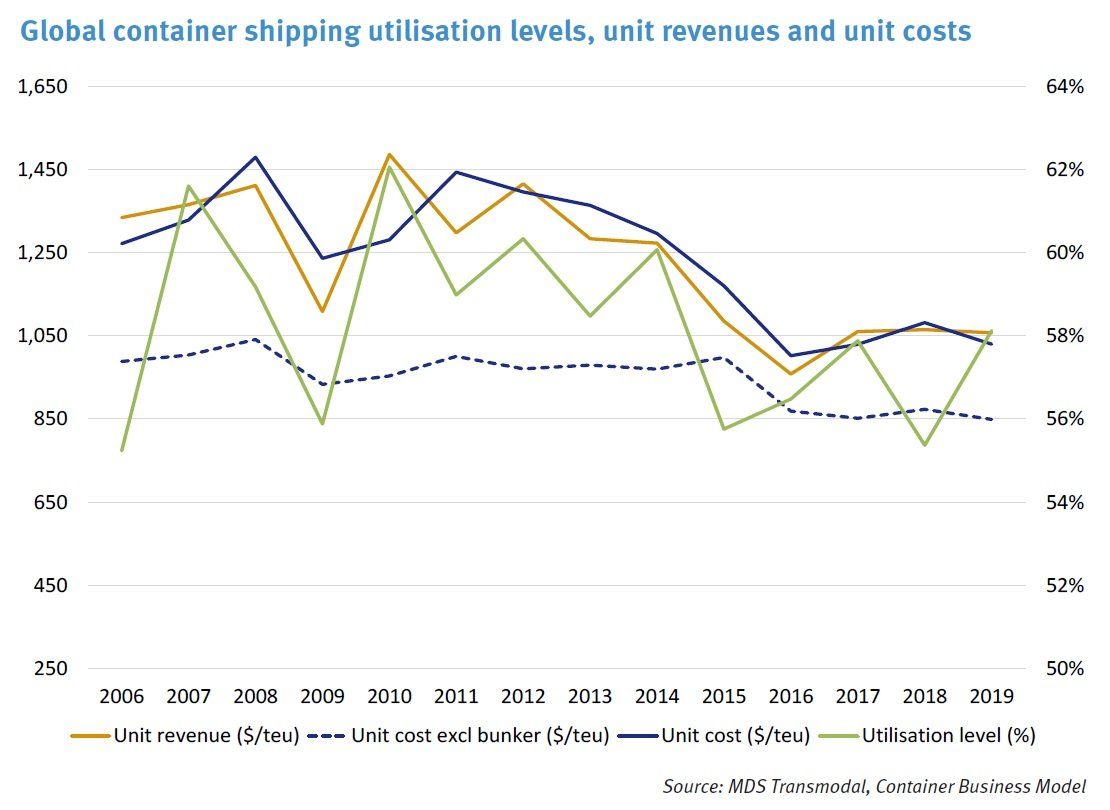

Globally, between 2006 and 2019, estimated unit costs have fallen by approximately 20% and bunker consumption per teu by circa 40%, with an efficiency gain of around $240/teu in real terms.

These trends have all been driven by a preference by most shippers for lower rates rather than higher speeds, explaining why round trips have extended from 56 to 68 days between the Far East and Northern Europe.

The decline in rates since 2014 cannot be explained by a fall in utilisation but by a fall in bunker costs, which have worked their way through to rates through competition, even though lines are now members of just three alliances.

The severe year-on-year fluctuation between unit costs and unit revenues as a result of short-term instability cannot help the lines or shippers to develop long term investment strategies — elasticity is such that relatively short-term fluctuations in utilisation create pronounced rate changes. The positive impact of consolidation on underlying costs and rates has not reduced the latter’s fluctuation.

Utilisation levels depend, of course, on supply and demand, whose trends can be forecast.

Supply can be readily monitored, including taking into account newbuilding programmes. Despite an overall decline of 15% in the number of services offered in the deepsea market between 2006 and 2019, the overall deployed capacity grew by 73%, with the number of vessels over 7,500 teu increasing eightfold during the same period.

Product development and efficient supply chains require shippers to be able to feel secure about the continuity and price of shipping services. It is indisputable that a sustainable industry based on long-term investments in supply chain assets requires confidence of all parties.

Global container shipping can approach optimum economies of scale and still operate with three independent global networks and so provide a competitive environment.

In principle, the larger shippers who trade over a wide range of routes will have leverage over lines where market shares can be high. There is less protection for smaller shippers seeking to retain their independence.

It would also appear that this has all been achieved without reducing overall connectivity across the global economy. The dependence of world trade on fewer operators is remarkable and it is most important to show that the different economies, large and small, remain well connected.

Based on the data provided to Unctad for the Liner Shipping Connectivity Index, MDST observes that China’s connectivity increased by 52% between 2006-2019 and by 40% between 2017-2019.

The Netherlands, the country with the highest LSCI in Europe last year, grew by 12% between 2017-19. Iraq, Qatar, Poland, Morocco and Albania saw their connectivity growing at the fastest rate between 2006-2019.

The handful of countries whose index fell over this period (including Yemen and Venezuela) accounted for less than 10% of the global population.

However, it is reasonable to assume that the vertical integration process could affect port connectivity. For the lines, shipping and terminal services represent a joint product.

Shipping about 170m loaded teu globally requires around 780m teu lifts at ports; high levels of transhipment are the price of achieving economies of scale at sea.

Stevedoring services represent around 35% of gate to gate costs. The integration of shipping and port business will affect the competitive position of individual ports and some nation states.

With the scope for more horizontal integration now limited, shipping lines’ eyes seem to be fixed on a more challenging target of becoming global logistics integrators.

This appears to be the aim of key ocean carriers. Maersk and CMA CGM, for instance, aim to offer a new more holistic service to their customers through vertical integration.

“The future will be very much about scaling the land side of the equation... We for sure have to do some acquisitions in the logistics space, primarily to gain capability and scale,” said Søren Skou, Maersk’s chief executive, as quoted last year by The Financial Times.

AP Moller-Maersk has implemented this strategy acquiring Vandegrift (customs brokerage and logistics business) and merging Maersk Line and Damco into one organisation, while CMA CGM has acquired CEVA Logistics.

Shipping lines have also been acquiring feeder companies and are now working closely with port operators.

By contrast, however, there are lines such as Hapag-Lloyd who want to maintain a more traditional approach and continue to offer just container shipping services to customers.

There are risks involved in the vertical integration strategy, including the scale of financial investments required, dealing with changes in the lines’ business model and associated costs.

However, the business opportunities are very appealing: getting closer to the cargo owners and having an influence on their choice of how to move their goods; further exploitation of scale economy and scope; extending market coverage.

Winning strategy

Which strategy will be the winning one for any individual line is difficult to predict as this will depend on the flexibility of shipping lines’ management in adjusting their view on how to move a box. The sea voyage will become increasingly just a part of the service they offer rather than the whole service.

The way in which information is shared and managed within the integrated entities will be vital, while technological innovation will be key.

Vertical integration and the further expansion of shipping lines into terminal operations can affect competition and choices for shippers, especially if all terminals within a port are controlled by the same company and that company is acquired or merged with a shipping line.

In these cases, the new entity will have an incentive to discriminate against other shipping lines by providing lower-quality services and applying higher port rates.

The commission might therefore consider the possible effects of vertical integration for the shipping industry as well as national competition regulators; while port authorities should monitor and evaluate carefully the private operators to whom they hand port concessions.

In addition to a deeper examination, through a careful and independent monitoring exercise, the commission can help the CBER gain acceptance by guaranteeing transparency through more detailed examination of the impacts, and using independent sources.

MDST believes this should not be difficult, given that charter, port and container hire costs are relatively easy to estimate.

Meanwhile, only bunker costs are unpredictable, but can be separately identified. Demand, too, can be estimated on a medium-term basis, while ship supply is more or less certain on a two- to three-year timescale. Rates can also be benchmarked.

Given the switch to cleaner, more expensive fuel, lines have another immediate interest in making bunker cost calculations available for independent assessment, to avoid unnecessary heat and misunderstanding.

There is more to be gained by transparency through using independent sources, which can be agreed upon between lines and shippers, to describe the business of container shipping.

This would help the parties to make informed decisions and reflect the fact that, for a shipper, the shipping line is a vital supplier with which a long-term relationship will contribute to maximising long term supply chain efficiency.

The key to achieving such long-term relationships could be the development of well-defined indices that cover demand, supply, utilisation, costs and revenues accompanied by interpretation of possible future impacts for the industry.