Changing Lanes: EU must use time ahead of CBER review wisely

- By Antonella Teodoro

- •

- 10 Nov, 2020

Vertical integration, carriers’ increasing affiliation with ports and terminals and the power asserted by the alliances are among a host of factors that must all be considered in detail by the European Commission ahead of the CBER’s review

THE European Commission decided in March to prolong the Consortia Block Exemption Regulation, leaving its terms unchanged for a further four years.

The regulation permits the exchange of information between shipping lines operating in consortia normally forbidden under general European Union competition rules. The exemption is available only to lines with less than a 30% share of the relevant market.

Introduced in 1995, and then revised in 2009, it was designed in a landscape quite different from today. Consolidation in the industry has been rapid.

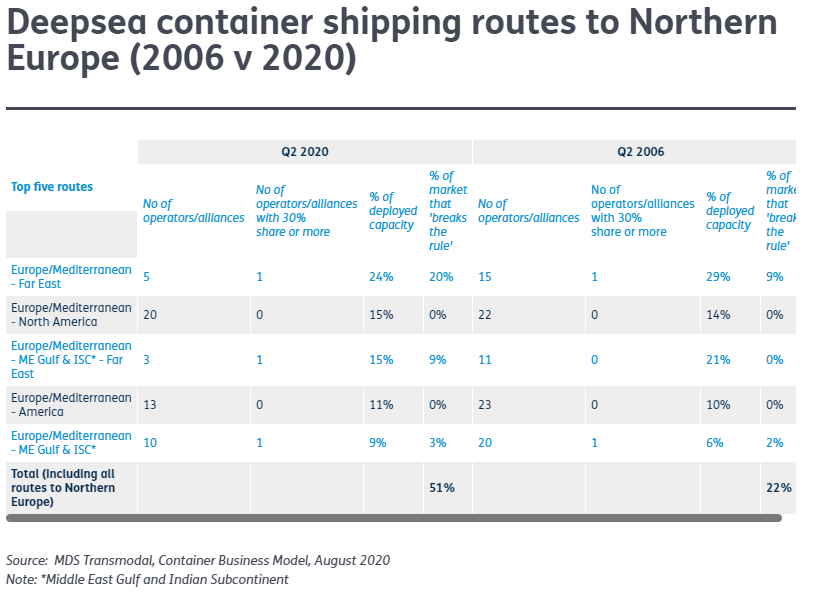

In 2006, the top 10 shipping lines controlled less than 60% of global deepsea capacity. None had a share above 20%. By 2020, the three major players controlled circa 90% of the global capacity deployed in the deepsea markets.

Acquisitions in the feeder market have reinforced this trend. In 2006, measured by deployed capacity, the four leading north European lo-lo lines were independent. Now the leading four are owned by deepsea lines or stevedores. Meanwhile, the lines themselves are extending their ownership in stevedoring and forwarding, which CBER does nothing to prevent.

Based on MDS Transmodal’s latest available model, allocating

estimated container flows to individual services alongside operating

costs and revenues, we estimate that between 2006 and 2020 estimated

unit costs fell by approximately 36% and bunker consumption per teu by

around 41%.

Overall vessel utilisation fluctuated but was generally consistent,

while rates fell by around 27% between 2006 and 2016. Lines chose to

operate much larger and slower ships after EU legislation eliminated

conferences, in order to compete vigorously on price. Liner round trips

have extended from 56 to a mean of 68 days between the Far East and

Northern Europe.

However, the decline in rates (particularly if calculated net of bunker costs) came to a halt after 2016, despite ship scale economies continuing to improve.

The positive impact of consolidation on underlying costs and rates appears to have been played out by 2016 and has not reduced rate fluctuation and, when corrected for bunker prices, net rates rose despite utilisation falling in the second quarter of 2020.

Despite an overall decline of 23% in the number of services offered in the deepsea market between 2006 and 2020, the overall deployed capacity grew by circa 70%, with the deployed capacity offered with ships of at least 7,500 teu increasing 12-fold during this period.

Product development and efficient supply chains require shippers to be able to feel secure about the continuity and price of shipping services. It is indisputable that a sustainable shipping industry based on long term investments in supply chain assets requires confidence on the part of all the relevant parties.

Based on experience through to 2016, global shipping could approach optimum economies of scale and still operate with these three independent global networks in a competitive environment. However, those unassigned to the carrier groupings would find it difficult to compete.

There too are severe barriers to entry. Independent owners of containerships are dependent on charters from alliance members for their employment. Larger independent carriers, who trade over a wide range of routes, may have some leverage where market share was high, however, there is less protection for smaller lines seeking to retain independence.

These barriers to entry provide an incentive to engage in more vertical integration. Shipping lines’ eyes seem to be fixed on the challenging target of becoming global logistics integrators. Or at least this appears to be the aim of key ocean carriers. Maersk and CMA CGM, for example, aim to offer a new, more holistic service to their customers through vertical integration.

“The future will be very much about scaling the land side of the equation... We for sure have to do some acquisitions in the logistics space, primarily to gain capability and scale” Maersk chief executive Søren Skou told the Financial Times last year.

AP Moller-Maersk has implemented this strategy, acquiring Vandegrift (customs brokerage and logistics business) and by merging Maersk Line and Damco into one organisation, while CMA CGM has acquired CEVA Logistics. Shipping lines have also been acquiring feeder companies and are now working closely with port operators, including in the area of data sharing.

There are risks involved in the vertical integration strategy, including the scale of financial investments required, dealing with changes in the lines’ business model and associated costs.

However, the business opportunities are very appealing. They allow carriers to get closer to the cargo owners (shippers) and influence how to move their goods, while also enabling further exploitation of economies of scale and scope, plus extended market coverage.

For the lines, shipping and terminal services represent a joint product. Shipping around 170m loaded teu globally requires around 780m teu port liftings; high levels of transhipment are the price of achieving economies of scale at sea. Stevedoring services represent just 35% of gate-to-gate costs.

The vertical integration of shipping and port business will affect the competitive position of individual ports and some nation states.

This process has a clear logic. It permits the development of integrated networks able to achieve efficient economies of scale that are of clear benefit if they reduce trade costs and improve global connectivity.

The sea voyage will increasingly become just a part of the whole service offering. The way in which information is shared and managed within the integrated entities will be vital — technology will be key.

However, vertical integration and the further expansion of shipping lines into terminal operations can affect competition and choice for shippers, especially if all terminals within a port are controlled by the same company and are acquired by or merged with a shipping line.

In these cases, the new entity will have an incentive to discriminate against other shipping lines by providing lower quality service and/or applying higher port rates.

The European Commission, national competition and other regulators might, therefore, consider the possible effects of vertical integration for the shipping industry. Public sector port authorities too should monitor and evaluate carefully the private operators to whom they award port concessions.

Given the switch to cleaner but more expensive fuel, lines have another immediate interest in making bunker cost calculations available for independent assessment, to avoid unnecessary heat and misunderstanding as the cost of switching to greener energy solutions become evident. As the pressure to switch to cleaner but potentially more expensive fuels intensifies, lines may find clients will demand a more transparent approach.

Increasing transparency through using independent data sources would help the parties to make informed decisions and reflect the fact that, for a shipper, the shipping line is a vital supplier with which a long-term relationship will contribute to maximising long-term supply chain efficiency.

The key to achieving such long-term relationships could be the development of well-defined measurement, through indices that cover demand, supply, utilisation, costs and revenues accompanied by interpretation of possible future impacts for the industry. As exemplified in this article this is certainly achievable.

There is a clear need for closer monitoring of the container shipping market in a post Covid-19 world and for the role and functioning of the CBER to be addressed, particularly the quality of data and information available to guide decision making.

MDS Transmodal is partnering with the Global Shippers Forum to launch a new quarterly report focusing on the features important to shippers and cargo owners as customers of the lines. The quarterly reports will also provide pointers to help the European Commission create a clearer policy framework for the shipping industry. Europe’s exporters and importers need a competitive and responsive shipping market, which is in the Continent’s wider economic and public interest.

The historical debate about container shipping has dwelt mainly on its status under competition law — and with good reason — however, all stakeholders in future will need to respond to the additional, multiple, challenges now confronting all stakeholders, including climate change objectives, the economic interests of the EU, contingency plans against future global economic shocks and the quality and competitiveness of shipping services offered to European exporters and importers.

There are three years before the next scheduled review of the CBER. This should be conducted with the assistance of better-quality data and better informed about the regulation’s costs and benefits to all parties. It should be undertaken in the wider context of European transport and industrial policy as well as the very different forces now shaping global trade and environmental priorities.

Changing Lanes is a regular commentary featured in the Lloyd’s List magazine