The end of the Consortia Block Exemption Regulation: What happens now

- By Mike Garratt and Antonella Teodoro

- •

- 09 Jan, 2024

Someone falling into a deep coma four years ago in December 2019 and re-awakening today might

be forgiven for believing that little had changed in the world of deep-sea containers. Container Trade

Statistics reported a 4.7% growth in global loaded TEU. The Shanghai Containerized Freight Index

was marginally higher. Maersk’s Q3 EBITDA was still around 14% of turnover. Mean ship size was up

by 11%. How misleading those initial observations would have been!

Over those intervening four years,

which incorporated a global pandemic, an initial fall off in traffic had been followed by demand

exceeding supply to such an extent that the

mean freight revenues had nearly trebled by

Q3 2022. Consequently, the lines made enormous profits that were (in part) used to extend

vertical integration into port terminals and

increasingly into door-to-door logistics.

However, having won their case four

years before, the lines had just lost the argument to retain the anti-trust legislation provided by the Consortium Block Exemption

Regulation (CEBR). The UK Competition

and Markets Authority has similarly decided

that the country will not establish its own

CEBR. And there’s the signed & sealed inclusion of much of the shipping industry in the

European Union Emissions Trading System

(EU ETS), effectively raising energy costs to

the lines by 40% for ships sailing between

EU ports (but not if sailing between other

ports – an invitation to develop ingenious

routing if ever there was!).

The age-old supply-demand

(different tune) dance

In so far as demand is concerned, the

trade statistics which feed our World Cargo

Database suggest that while the European

market has been depressed in 2023,

the global pattern of 3% per annum growth

is re-establishing itself; exports from the Far

East are now growing, including to Europe.

We estimate that at its peak, the very high

freight rates that drove as much as 7% of

cargo normally containerised to alternative maritime, air, or overland modes – but

this level of diversion has now been halved.

Figure 1 indexes the changes in scheduled deployed capacity, fleet capacity,

demand, and mean revenue per TEU over

the last few years (with Q1 2019 as the baseline). A supply shortage in late 2020 accelerated rates that peaked over a year later when

fleet capacity was already creating a capacity

surplus. Demand fell back, and only now is

returning to the levels of three years ago.

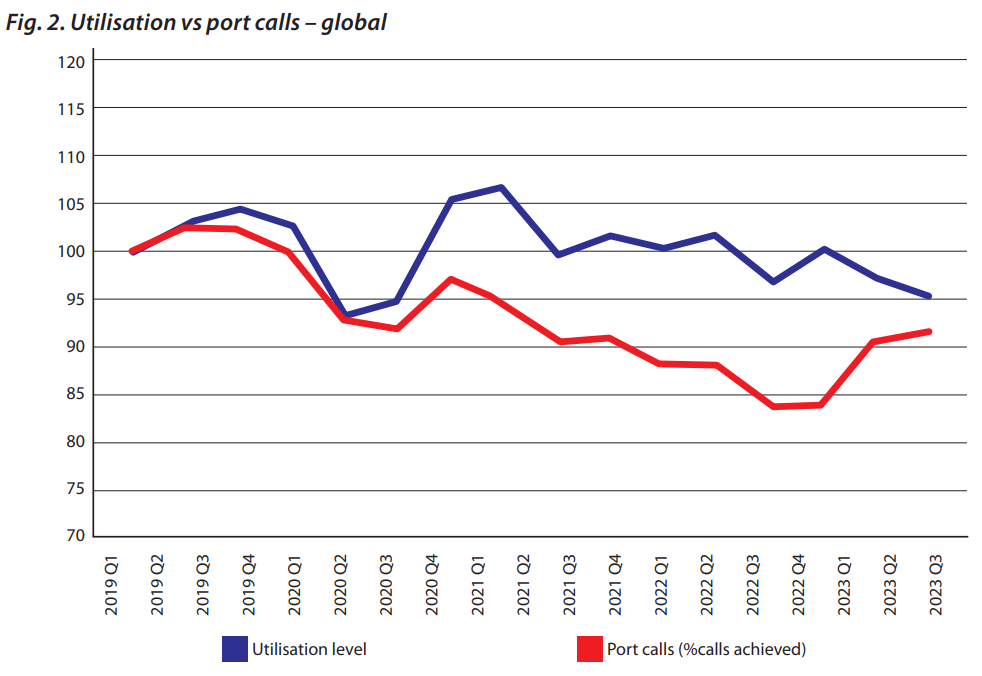

The impact of the coronavirus pandemic

and the management of fleet capacity led

to the curious feature of utilisation levels

(demand/supply) falling as the number of

ports the lines called at relative to ‘scheduled

expectations’ also fell, a significant slump

in service quality that is only recovering in

the second half of 2023.

Our forecasts for

all deep-sea containerised trades over the

next five years reflect the gradual pick-up in

demand being experienced as 2023 comes to

an end (most marked on the Pacific).

However, this level of growth appears

unlikely to match the additional capacity that has recently and is currently being

built. The lines offered less deployed capacity during COVID-19, which drove rates

up. Ironically, as ship queues and capacity

challenges in the ports have been resolved,

the lines have more ships on order than

demand may justify over the next three years.

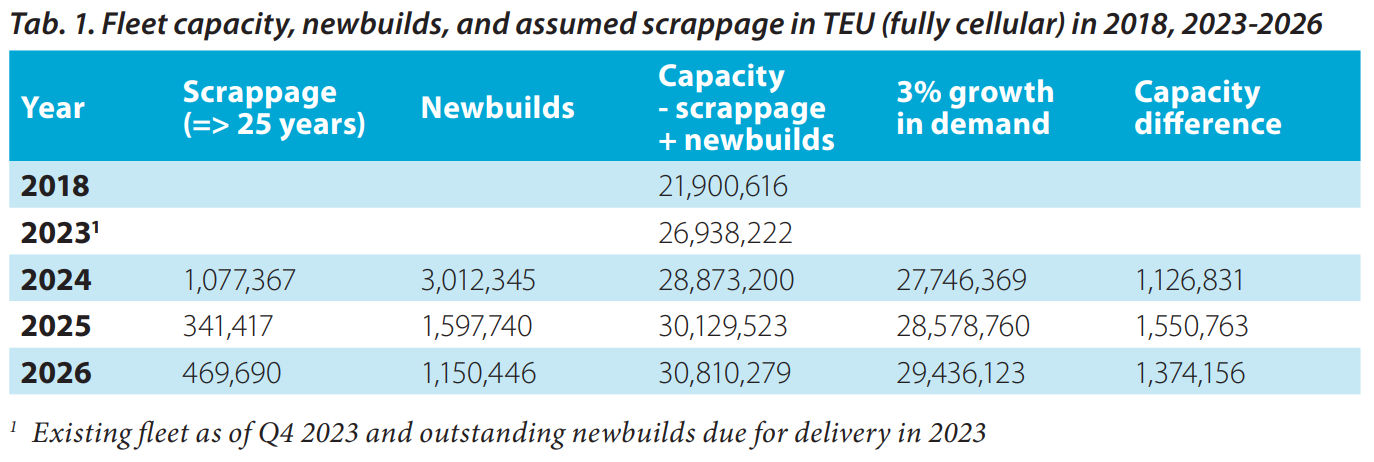

Table 1 describes our current estimates

for fleet supply (including newbuilds and

scrappage) and the capacity required to

address a yearly 3% growth in demand

(assuming ships continue to operate at

current speeds in existing strings). If the

way vessels are deployed remains the same,

then we estimate excess fleet capacity to be

around 4.5% in 2026 (1.4m/30.8m TEU of

fleet capacity) compared with today.

In practice, the lines will be able to absorb

some surplus fleet capacity through further

speed reductions to re-optimise given the

impact of the EU ETS, increasing the proportion of the fleet deployed on ‘multi-regional’

services (e.g., Europe-Gulf-Far East), more

lines operating services independently, and

through adding ports to rotations to reduce

feeder costs (and potentially game-play the

EU ETS to minimise nautical miles between

ports in the European Economic Area).

Scrappage may also accelerate.

An important question is the overall

impact that the end of CEBR will have.

MDS Transmodal’s role in this debate

was to provide the European Commission

(COM) with statistical analyses on fleet

deployment and market shares.

Crackdown?

The lines lost the argument to retain

CEBR because COM decided that providing the liner business with anti-trust privileges that exceeded those available to other

sectors did not pass the five tests (of effectiveness, efficiency, relevance, coherence,

and EU-added value) it set

and, crucially,

did not protect shippers (i.e., consumers)

when a crisis occurred.

While a number of European trade associations collaborated to also argue against

CBER

because of the high levels of vertical integration taking place, the most dramatic statement against the lines probably

came from another jurisdiction. President

Biden’s March 2022 State of the Union speech

included this passage:

“See what’s happening

with ocean carriers moving goods in and out

of America. During the pandemic, about

half a dozen or less foreign-owned companies raised prices by as much as 1,000% and

made record profits. Tonight, I’m announcing

a crackdown on those companies overcharging American businesses and consumers.”

So, will this legal change make a difference?

The degree to which the World Shipping

Council campaigned to retain CEBR suggests that it will make a difference. Then

again, it may be that the major lines were

already adapting to a decision they had

anticipated. The 2M Alliance will complete

its break-up in 2025. The very largest carriers

are likely to operate their global networks on

a stand-alone basis or with support from the

smaller players; there may even be a further

consolidation because the nine leading lines

cannot each sustain global networks alone.

While for smaller markets, lines may be able

to make a case that market shares above 20%

are in the wider interest, this will not be the

instance for the larger markets.

The impact may extend beyond the

lines themselves. Page 32 of the COM staff

working paper discussed the relationship

between CEBR and the container terminals

that the leading lines also control, implying

that CEBR also protected the relationship

between lines and these terminals, and its

end could raise questions about the rights of

equal-term access. Such uncertainties may

be compounded where different regulators

(on a trade route) have differing rules; some

(e.g., Singapore) allow up to a 50% market

share for a given consortium.

To raise awareness and to question

Rather than make a firm prediction,

we put forward three potential outcomes.

Firstly, one that does not favour the lines

and to which an excess supply weakens

their position. The uncertainty that may

apply to the relationship between terminals

and lines post-ending of CEBR may play to

the advantage of the non-liner major stevedores, who did not have the leverage to

make super profits during COVID. These

stevedores seek to develop a closer relationship with shippers, which will improve

their ability to provide value-added services

and onward transport services (directly or

by sub-contract). This is already happening; stevedores own companies feedering

containers (DP World – Unifeeder, Peel

Ports – BG Freight Line, Abu Dhabi ports

– Safeen Feeders, etc.), and ports contract

for space with railroad operators. At the

same time, port-centric distribution hubs

secure cargo to an individual port. The

lines themselves come under increasing

pressure to offer the most cost-efficient

services, leading to further consolidation of liner services. Non-vessel operating common carriers expand their port-centric distribution centres and, likewise,

their capacity purchasing from the lines.

Quite clearly, this may not be attractive

to some of the shipping lines. The ability to

make profits by charging an economic rent

to pass through a port will pass to the ports

themselves. The step taken at Jebel Ali is

worth noting, where DP World announced

that cargo owners, not the lines, will pay

terminal handling charges.

The second scenario favours the lines.

If market shares do not exceed 20%, an individual shipping line will continue to vertically integrate (including with terminals,

inland transport services, and door-to-door

logistics). In an environment where scale

economies are crucial, any share less than

20% could, therefore, be uncompetitive, and

a very small number of look-alike global

vertically integrated operators emerge. Ports

whose terminals are not included in such

networks may find it challenging to remain

in the market. Individual lines (and two of

the existing ones already reach this scale)

are supported by a range of sub-contractors

(feeders, third-party logistics, etc.) who are

effectively rate takers; the advantage will lie

with the lines. The relatively broad definitions of markets may be such that within

these, sub-markets remain oligopolistic.

Outcomes may not be so extreme, and

much may depend upon the legal interpretation of the new regulatory environment.

The World Shipping Council may have

a point that change will generate legal uncertainty (but that’s in the nature of change).

Thirdly, a possible course of events in

which nation-states and regulators take

a more proactive approach. Given the problems shippers faced during the pandemic,

the decision to terminate CEBR despite the

position that the lines have taken, and the vast

challenges faced to decarbonise the industry, global bodies may choose to examine

whether the current industry structure serves

the public interest to promote trade. Such

an examination may consider that regular

and reliable liner shipping services should

be seen as a global trading utility, providing

a minimum level of connectivity, frequency

and reliability (including to emerging economies). In these circumstances, it could be that

lines will find themselves being obliged to

offer minimum levels of service to individual

nation-states to be authorised to operate at

ports in their countries.

We do not suggest which, if any, of

these ‘travel directions’ might be followed.

However, one of the effects of the industry’s

reaction to the pandemic has been to raise

awareness of the vulnerability of world trade

to investment and operational decision-making by a relatively small number of companies and to question the level of resilience the

industry offers.