This article offers an overview of UK maritime freight in a global context across various cargo types since 2018. UK port throughput has generally declined driven by factors such as Brexit, the decline in North Sea oil and decarbonisation of the UK’s energy mix, and global economic disruptions. Container traffic experienced the greatest reduction, while other types of cargo such as dry bulk, liquid bulk, and roll-on/roll-off (RORO) freight also experienced notable declines.

The volume of maritime trade through the UK’s ports is essential to the overall economy; in 2021 about 95% of international freight traded with the UK was moved by sea[1].

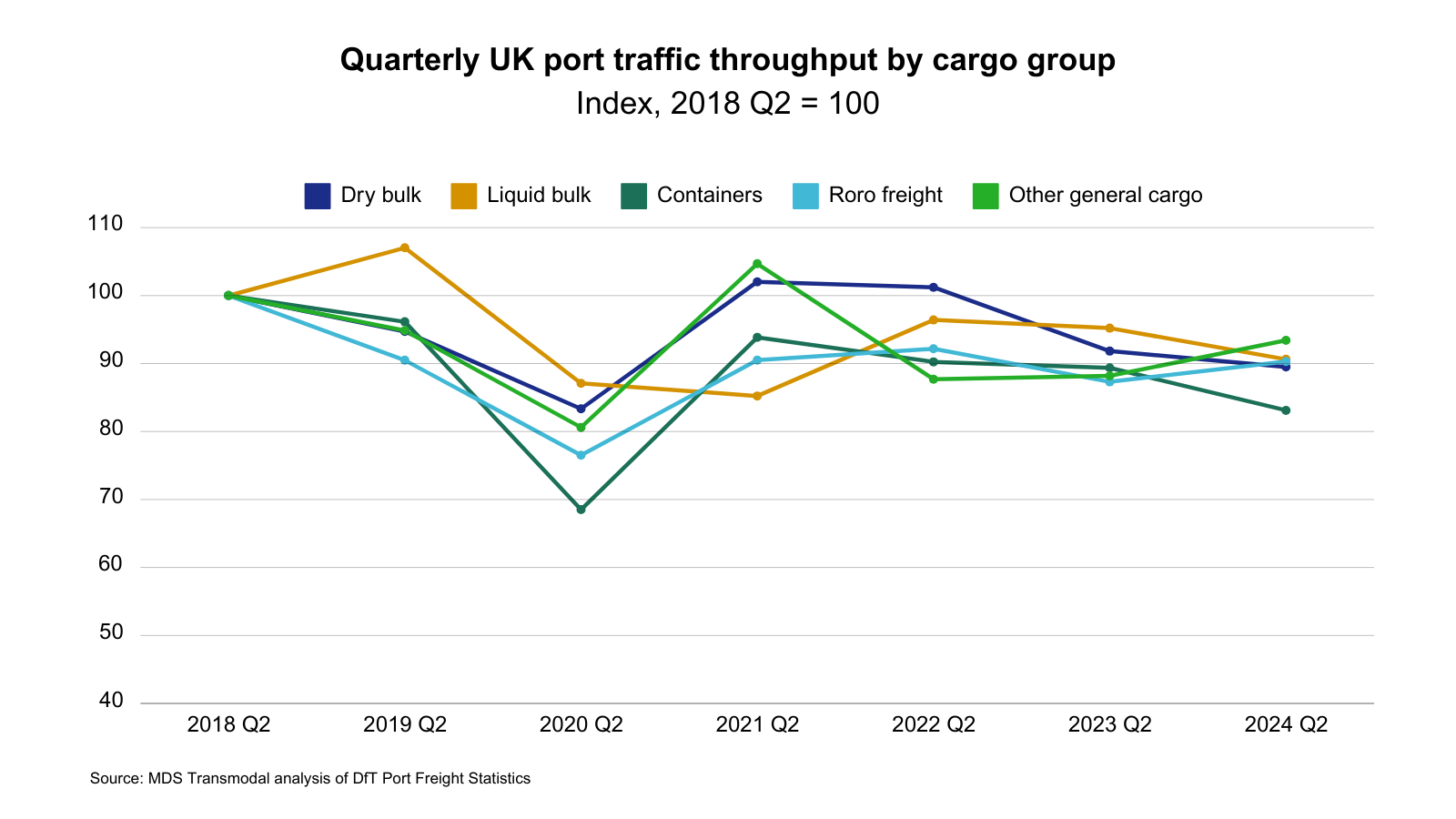

The above chart shows changes in UK port traffic by cargo group on an indexed basis over the last six years. The overall trend has been a reduction in port throughput, with the largest decline of 17% in containers. Dry bulk, liquid bulk, and RORO freight had comparable reductions of 10% while other general cargo reduced by 7%.

Volumes in 2024 Q2 are lower than pre-pandemic levels in 2018 Q2 but represent a recovery from the drop in 2020 Q2, which was experienced across all cargo groups. Compared to the same quarter last year, RORO freight and other general cargo had a slight increase, while all other cargo groups decreased in tonnage.

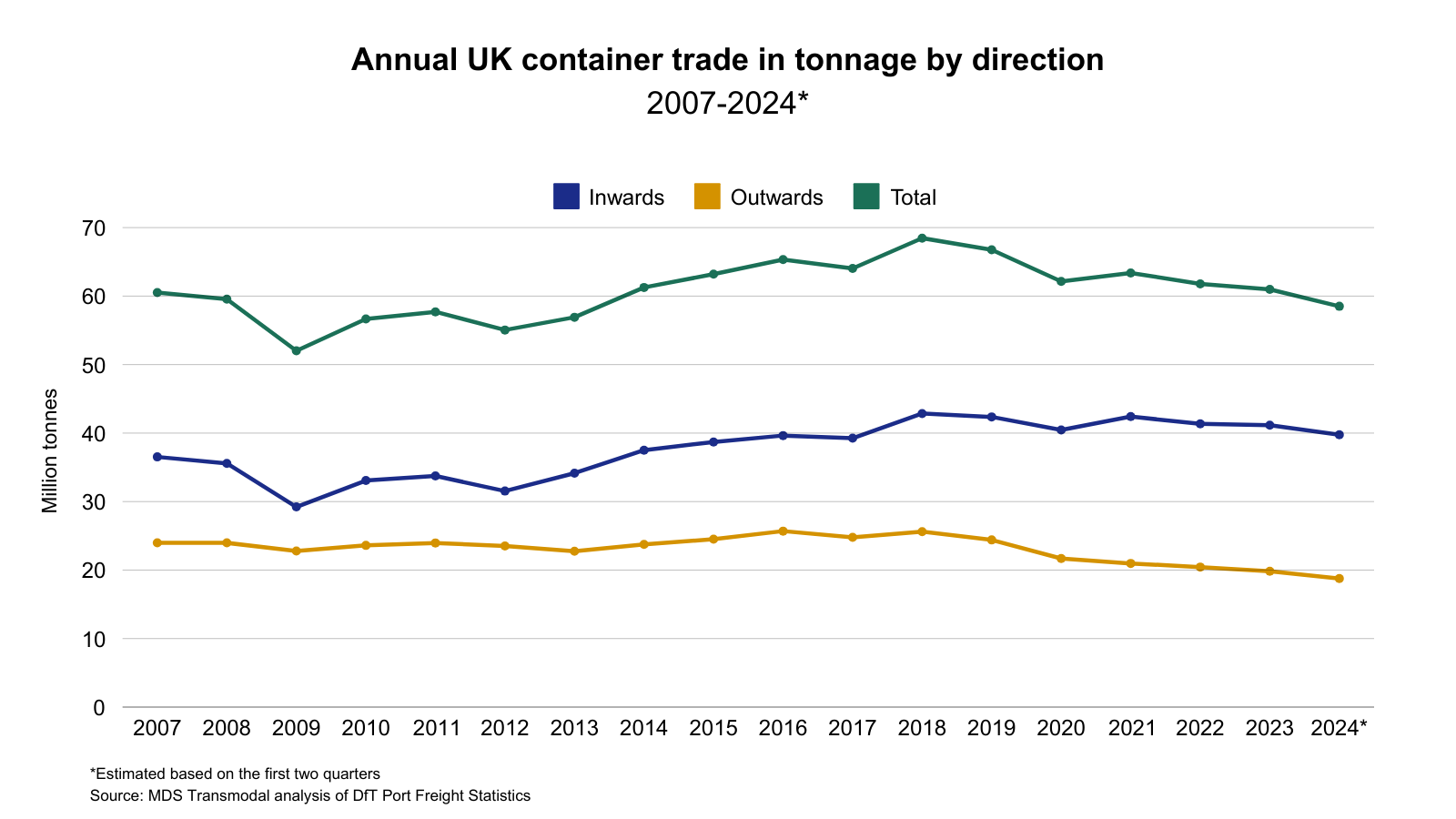

The trend in UK container trade (both deep sea and short sea) by direction sheds further light on the changes in imports and exports.

Container shipping is integral to international trade, moving vast quantities of goods every day. A wide range of goods can be transported in containers; those with high international demand include machinery, textiles, electronics, and perishable goods like fruit and vegetables.

From 2007, total container trade in the UK has fluctuated with major global events that affect both consumption and supply as evidenced by a fall in volumes during the 2008-09 financial crisis and a slight decrease during 2019 and 2020 coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic as factories were forced to close. A recovery in 2021 was driven by increased imports (with household income being funded in part by the government and consumers unable to purchase many services) but was followed by a fall in volumes until 2023 and is expected to continue in 2024.

By direction, exports dipped between 2018 and 2024 as the

economy adapted to an EU Exit environment. On the other hand, imports, which

stand at double the volume of exports, recovered to pre-Brexit levels in 2021

but have since slipped.

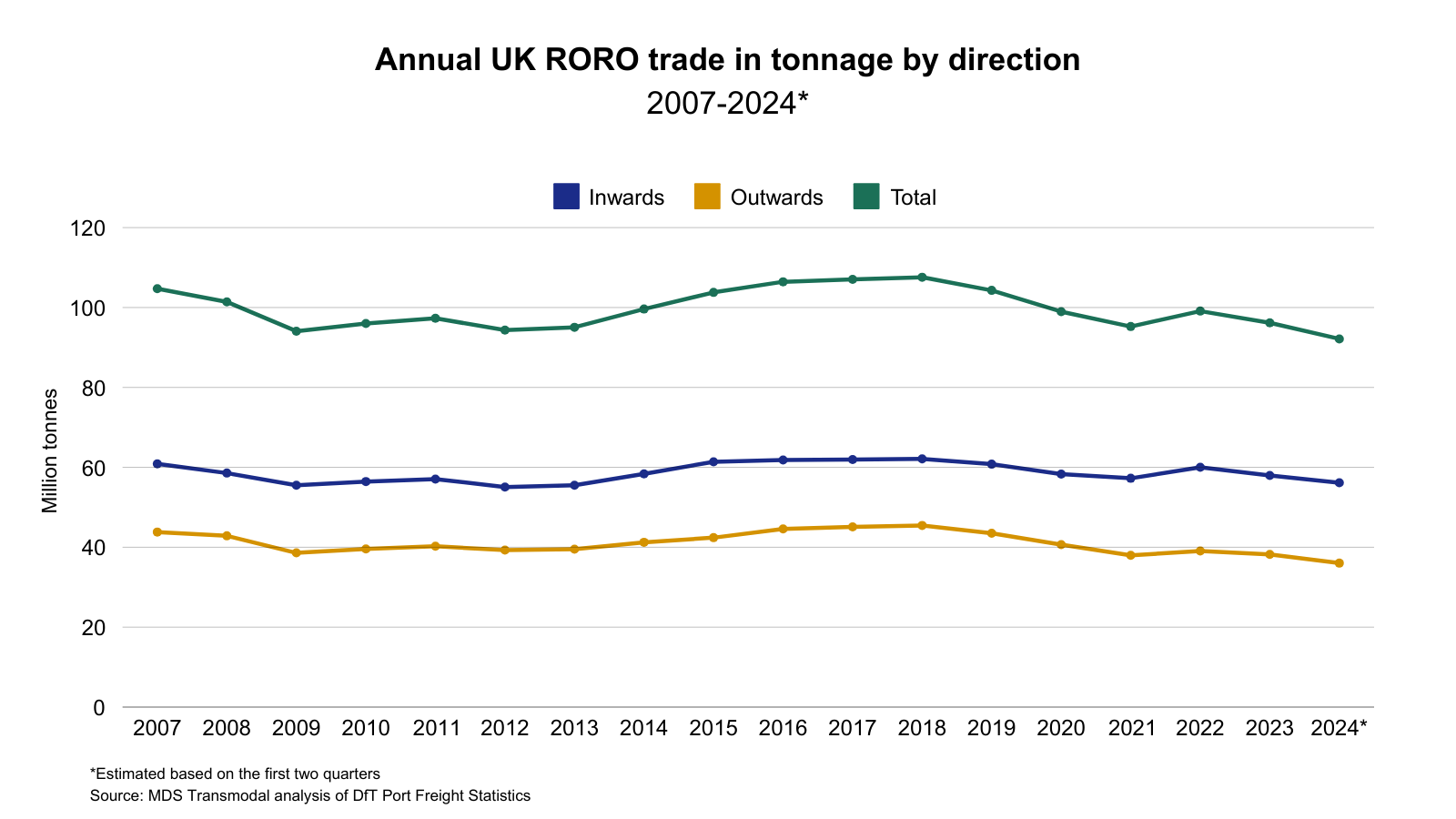

Roll-on/roll-off (RORO) freight is transported by ships with dedicated ramps designed to carry wheeled cargo. This allows vehicles to be driven on and off the vessel, or containers to be wheeled onto the ships on special trailers.

Various commodities are transported using RORO shipping such as cars, machinery and heavy equipment, but most is general cargo which can be transported in containers and is between Great Britain and the European continental mainland and Ireland.

Since 2007 RORO trade by direction recovered after the financial crisis but is yet to recover fully after the impact of COVID-19 and EU Exit. Growth in 2022 traffic is likely a consequence of restocking after COVID-19. The just-in-time manufacturing model allowed companies to cut excess inventory and achieve efficiency savings by keeping suppliers on short notice and only producing inventory as needed. However, during COVID-19 supply chain disruptions led to shortages and then EU Exit led to additional trade barriers which pushed companies to the just-in-case model instead, whereby a certain inventory level is maintained to avoid running out of stock.

This is a possible explanation for the rise in traffic in 2022, followed by a fall in 2023 as a result of overstocking. Traffic in both directions is expected to remain at a lower level in 2024 than in 2007.

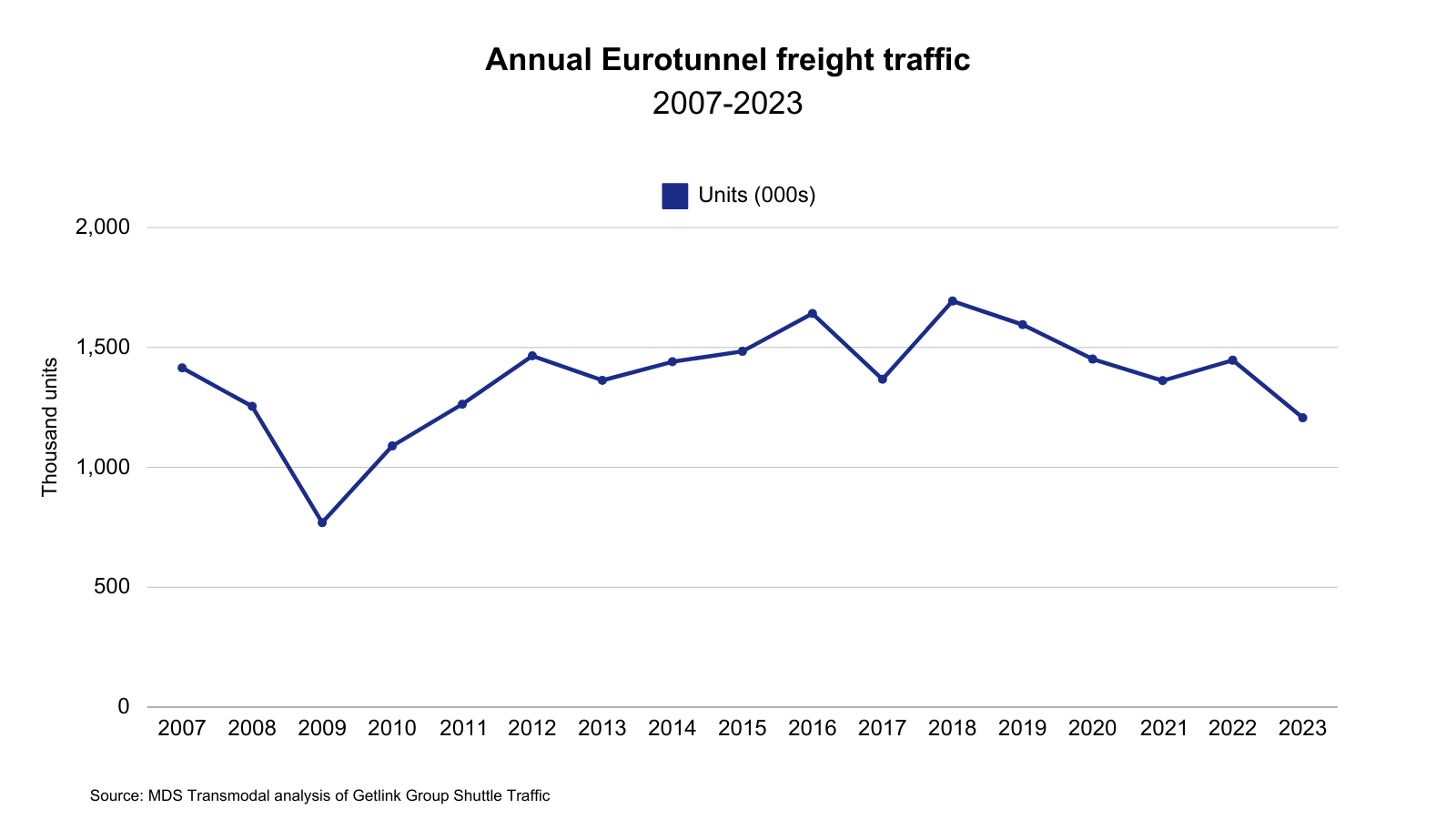

The container and RORO port traffic analysis uses data sourced from the Department for Transport, collected from port operators, shipping lines, and agents. While not a port, Eurotunnel Freight is a significant route for UK trade with the Continent. An examination of Eurotunnel data shows a similar trend to that for RORO via ports, with a decline in the number of units from 2018 followed by an uptick in 2022 and a subsequent decrease in 2023.

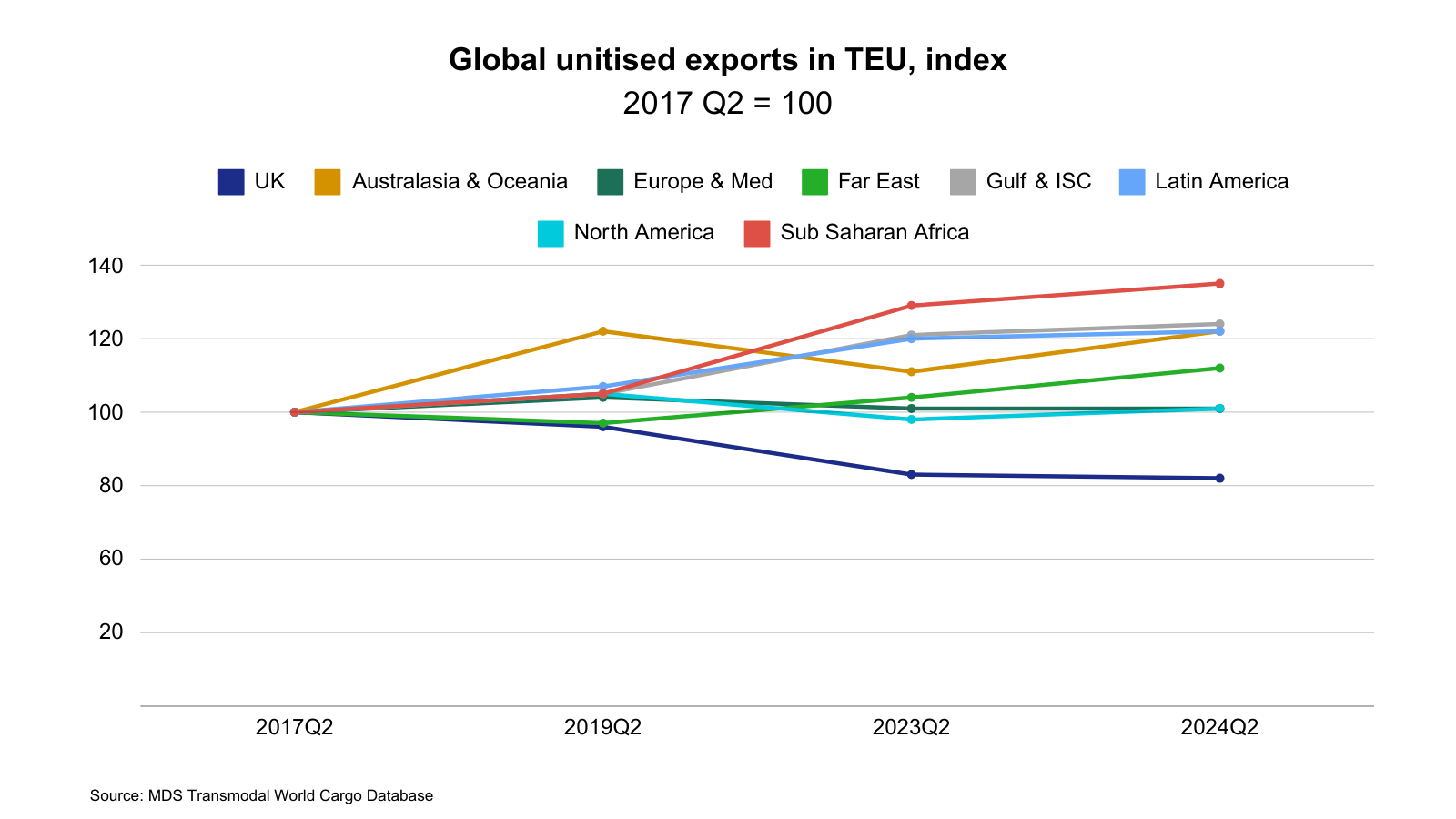

Comparing the regional performance of global unitised imports and exports reveals the relative performance of the UK since the pre-Brexit year of 2017. This chart shows the trend in global unitised exports, measured in TEU, across different regions from 2017 Q2 to 2024 Q2. The index is set at 2017 Q2 to allow for a comparison of relative export performance over time.

Since 2017, UK exports show a downward trend, decreasing to 2023 Q2 and levelling out at around a 20% decrease to 2024 Q2, remaining below pre-EU Exit levels. On the other hand, other regions either flatlined or experienced growth since 2017.

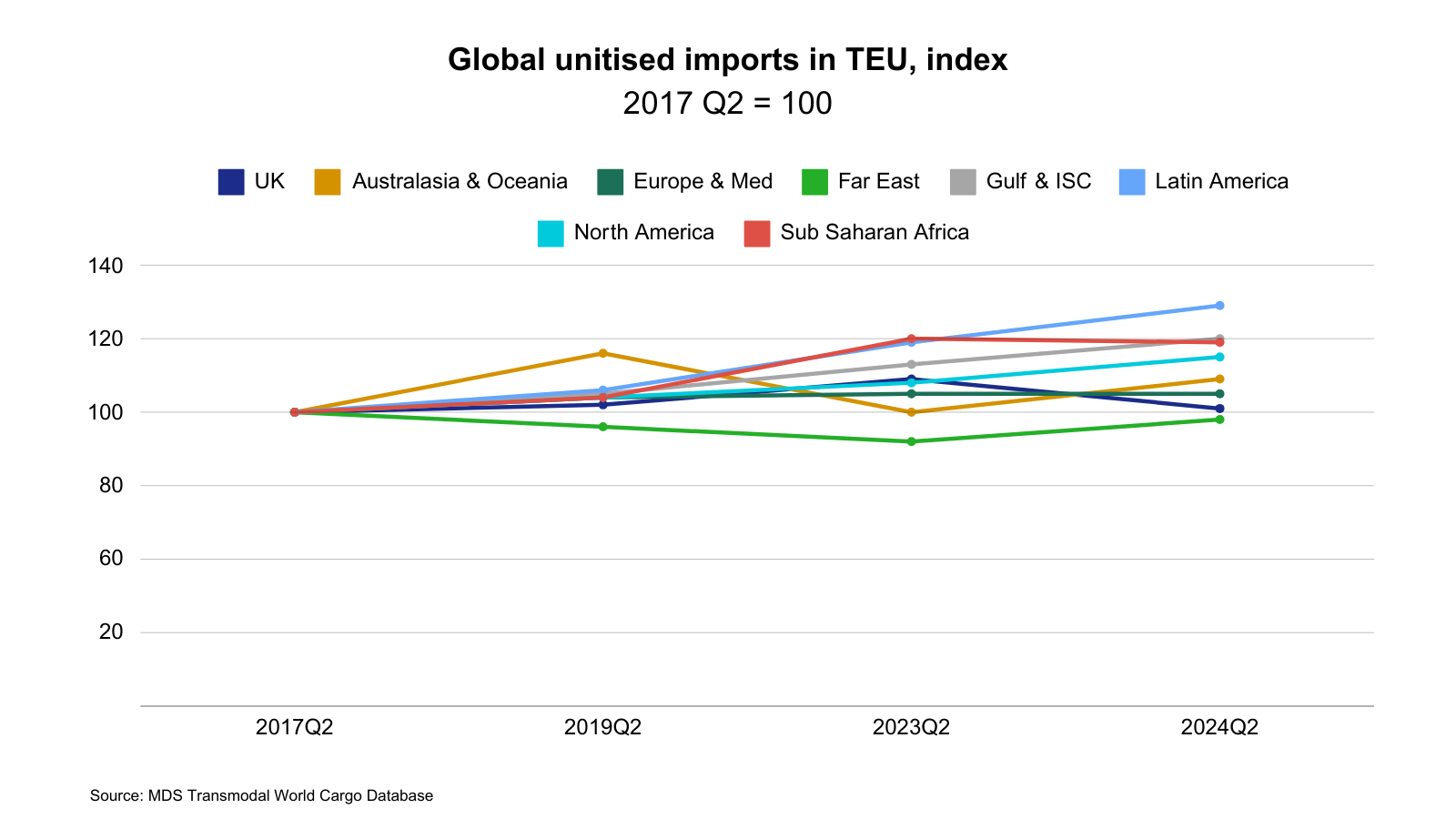

The UK’s imports have seen minimal growth from 2017 Q2 to 2024 Q2, remaining close to the 2017 baseline. This is mainly due to changes in the UK’s trading relationships due to the UK’s exit from the EU, resulting in increased import costs and logistical challenges with European trading partners.With

the exception of the Far East, imports have increased into all regions and

exceeded 2017 levels.

Conclusion

The analysis of UK freight trends up to 2024 Q2 reveals a decline in the UK's share of global unitised trade relative to pre-Brexit levels. This downward trend in port throughput and container trade reflects shifting trade patterns, including Brexit's impact and global supply chain disruptions due to COVID-19. While exports have declined since 2017, mainly due to the introduction of trade barriers with its main trading partners, imports have held up better (due to, in particular, the UK’s need to import food from the EU) but are now falling back to 2017 levels. Overall, these trends suggest that the UK is facing challenges in maintaining its position in global trade in physical goods.