Will the coronavirus pandemic end globalisation?

The pandemic, following the 2008 financial crisis and the 9/11 attacks, has strengthened arguments for nationalism, while highlighting the fragility of the global supply chain. However, the cost of abandoning the tried and tested model of globalisation will create a further shock to an economic system already under immense pressure at the hands of the virus

Failure to repair the current liberal trade system may have more severe economic consequences in the long term than those caused by the pandemic

The health crisis has brought major disruption to supply chains, prompting more companies to seek alternative suppliers.

TARIFF reductions, the alleviation of trade restrictions, and technological progress in transport and communications led to world trade in non-carbon goods growing from 4.2bn to 8bn tonnes in the decade to 2019.

Globalisation and pandemics are old acquaintances. For example, the introduction of “quarantine” measures in Venice some 600 years ago. But air travel, the internet, trade liberalisation and falling freight transport costs have made countries much more vulnerable to extreme health or financial events on the other side of the world.

The coronavirus pandemic coming in the wake of the 2008/2009 financial crisis and the 9/11 attacks have strengthened arguments for nationalism once more, while highlighting the fragility of the global supply chain.

Governments are now preoccupied with establishing policies to protect their citizens from the coronavirus. However, a failure to repair the current liberal trade system may have more severe economic consequences in the long term than those caused by the pandemic.

The trend towards regional trade agreements such as the Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership represents a step away from the present more integrated global trade system and will leave barriers in place for non-partner countries, reducing overall global standards of living.

The current health crisis has also disrupted supply chains. Companies are looking for alternative suppliers at home, accepting higher prices and therefore potentially leading to a reduction in living standards. The changes in suppliers might become permanently fuelled by an increasing political drive to be less dependent on international trade.

For governments, however, to feel confident in excluding the idea of rejecting a departure from liberal trade, and convince the electorate on why this is a more advisable course of action, they too, need to recognise how damaging the ending of liberal trade would be.

But merely to guarantee a longer life to liberal trade should not be seen as the end of the process. Several of its current features need adjustment. Most important is the reformation of the World Trade Organisation, but also a need for national policies to respond to globalisation and its imperfections.

One of the major factors weakening the role of the WTO is the increasing influence played by China on a global stage. When the WTO’s members allowed China to join the organisation in 2001, the western economies believed that its membership would sustain and accelerate its transition into a market-based economy, bringing socio-economic advantages for China as well as for the countries trading with it.

It is though undeniable that China’s openness to the world has had positive impacts. Cheaper exports from China have been an important factor in lowering the cost of living in Western economies, while millions of Chinese have been lifted from poverty. However, China has not become an economy based upon the market rules practiced in the west as envisaged in 2001, and is never likely to be as its government maintains its central role in its economy.

A particular example of WTO rules that are difficult to implement with respect to China concerns public subsidies.

While the WTO allows governments to impose tariffs on goods where explicit production subsidies apply, it would not allow indirect subsidies such as below-market interest rates on credits given by state-owned financial institutions.

Many in the West argue that the cost of free trade has been unchallenged. The major area of contention is the loss of manufacturing jobs, which is a longstanding political issue.

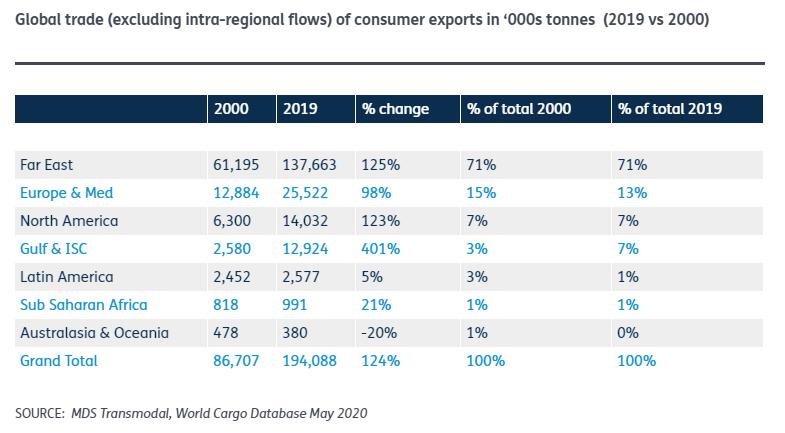

The table below shows how exports of consumer goods has grown rapidly in eastern countries compared to the European countries since the turn of the century, with their share of the total trade relatively unchanged at above 70%.

The pandemic and the disruption in supply chains that have occurred from the restrictive measures put in place to limit its spread, have caused critical shortages of essential goods and materials highlighting the “dependency” on factories located in the Far East. This has encouraged countries to think more about safety and self-sufficiency, powered by popular opinion rather than the thoughts of economists.

However, one should not ignore the advantages that liberal trade has brought. It has increased competition, promoted innovation and efficiency, while providing the sustained the diffusion of knowledge and movement of capital. Consumers also benefit from a greater variety or choice of goods.

Rejecting globalisation would mean rejecting these positive impacts but, more importantly, the cost of abandoning the existing networks and associated investments would itself create a further shock to an economic system already under immense pressure making the current situation worse.

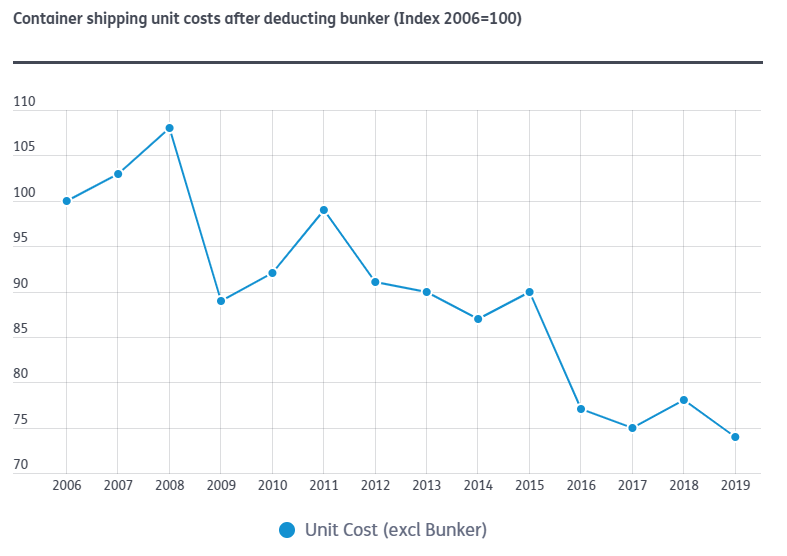

The consolidation of shipping lines and the deployment of larger and more efficient vessels offered on deepsea routes have led to a substantial reduction in maritime costs (as seen in the chart below) to the benefit of the global economy.

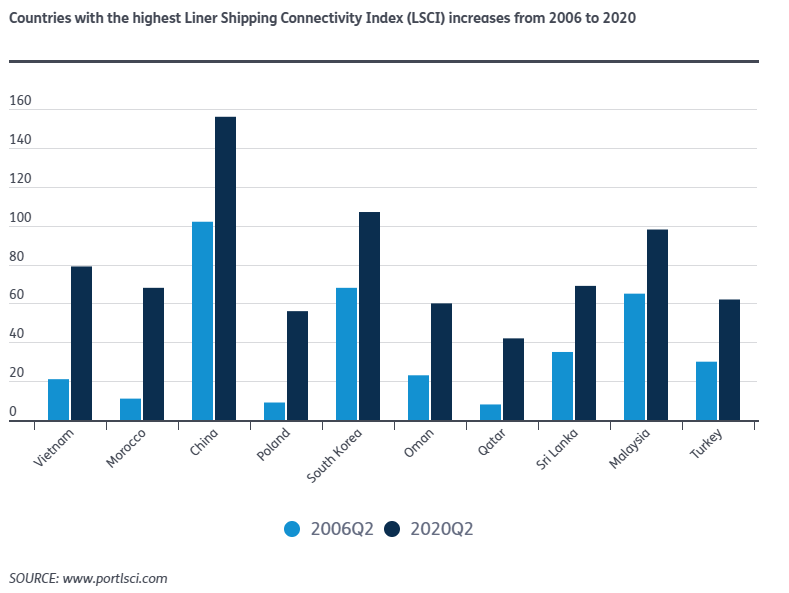

Less integration of global trade could affect levels of maritime connectivity, which could be damaging especially for the developing countries.

A reduction in maritime services offered by the shipping lines, to adapt to declining trade flows, is likely to affect the liner shipping connectivity of sourcing countries both in terms of intercontinental as well as intra-regional feeder calls.

This could make economic development harder for these economies. The chart below shows the top 10 countries with the highest Liner Shipping Connectivity Index increases between 2006 and 2020.

While abandoning liberal trade would be a mistake, not using this moment of crisis to reform the system in which it operates would be a missed opportunity to improve its possibilities.

First published on Lloyd's List website June 2020