Red Sea disruption drives new routes and regional opportunities

Connectivity Gains Across Regions

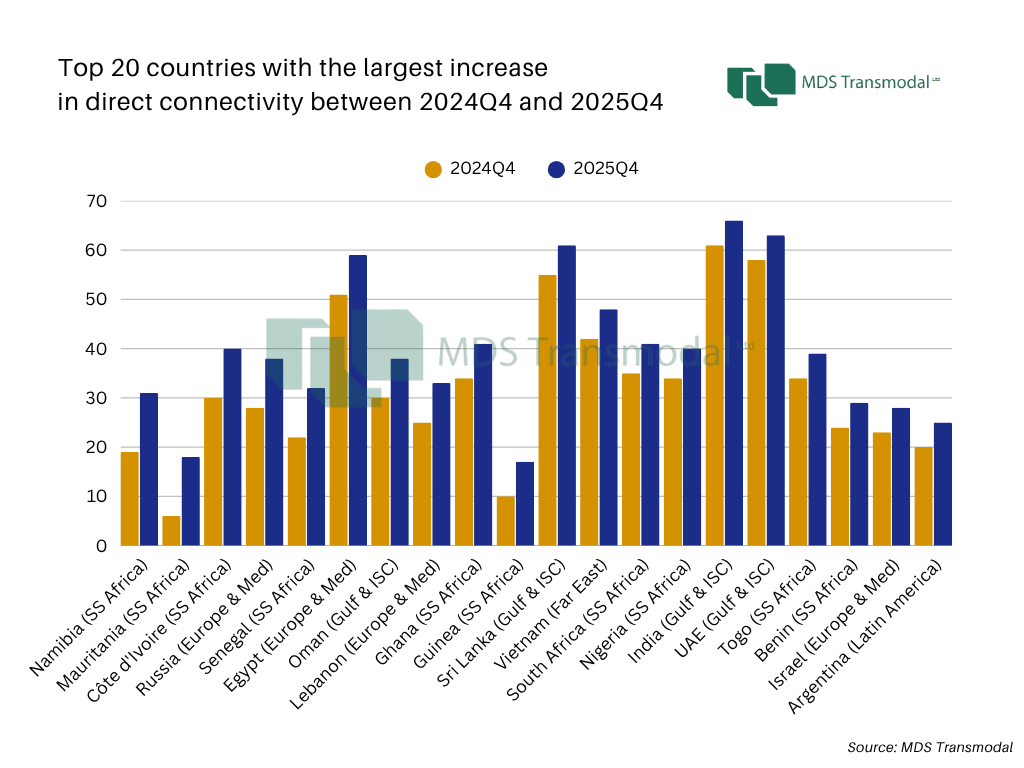

Namibia and Mauritania led globally, adding 12 new direct country connections each, followed by Cote d’Ivoire and Senegal (+10). These trends reflect a strengthening of West African liner networks, where carriers are adding direct calls to meet rising demand, diversify transshipment dependencies, and respond to the ongoing Red Sea rerouting.

Outside Africa, Gulf and South Asian markets (including Oman, Sri Lanka, India, and the UAE) recorded steady improvements, consolidating their role as key regional and intercontinental hubs. In the Europe and Mediterranean region, Egypt, Lebanon, and Russia stand out, reflecting service shifts linked to Suez Canal traffic and evolving geopolitical trade routes.

Global Connectivity Reaches Post-Pandemic High

By Q4 2025, global direct connectivity reached 2,263 country pairs (direct container shipping links between two countries), the highest level since Q3 2023, following the start of the Red Sea crisis. While still below the all-time peak of 2,598 pairs in 2016, the rebound signals renewed expansion after years of consolidation.

Environmental Regulation and Ship Deployment

Environmental rules increasingly influence vessel deployment. Under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), the carbon cost for a ship calling at an EU port is calculated based on the voyage from its last qualifying port outside the EU (or the previous EU port) to the EU destination. This encourages operators to consider non-EU hubs, such as African ports, to optimise emissions costs, shaping route choices and the durability of newly established connections.

Looking Ahead: Red Sea Disruption and Global Maritime Networks

The 2025 the data highlights a more resilient and distributed liner network, with new direct connections emerging in developing markets and mid-tier gateways. The Red Sea disruption is not expected to be fully resolved soon, as major carriers continue to adjust deployments to mitigate risk, reflecting a cautious approach to the region. Even if the Red Sea eventually reopens for regular navigation, carriers are likely to maintain alternative routings and hubs, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where they aim to manage overcapacity and maintain operational efficiency. Ship rotations are being adjusted where possible to better align with demand.

Even as security in the Red Sea gradually stabilises, it is unlikely that major carriers will fully abandon the alternative routings they established during the disruption. Both corridors – the traditional Red Sea/Suez route and the southern/secondary routes via Sub-Saharan and South Asian hubs – are likely to coexist, serving complementary purposes. The Suez route offers shorter transit times and established infrastructure, ideal for high-priority or time-sensitive cargo, while the alternative routes provide risk diversification, access to emerging markets, and operational flexibility. Carriers can dynamically allocate vessels based on demand, transit times, and cost considerations, while ports along both corridors continue to develop specialised roles. This dual-routing approach not only enhances network resilience but also allows carriers to optimise fleet deployment, manage overcapacity, and respond to environmental and regulatory pressures, suggesting that many of the new connections forged during the Red Sea crisis may persist long-term.

These strategic adjustments, combined with evolving demand patterns, suggest that many of the new routes and connections established during the crisis may persist, creating long-term growth opportunities for ports and regions that gained prominence during this period.

Stay ahead of shipping lines' evolving strategies with insights from our Containership Databank. Reach us at web.enquiries@mdst.co.uk.