Taxing times: Is road pricing the future for freight taxation?

In the 2025 Budget the Chancellor announced a proposal to introduce a crude form of distance-based taxation for electric and hybrid cars, with the introduction of an Electric Vehicle Excise Duty (eVED) of 3p per mile for electric vehicles and 1.5p per mile for plug-in hybrids from April 2028. Taxation of HGVs was left unchanged, probably because electric HGVs represent only 0.02% of the total registered fleet.

In our pre-Budget article on the taxation of road haulage we explained how the transition to road pricing is not just a fiscal necessity—it’s a strategic imperative. As we move towards net zero, the UK must rethink how it funds its road infrastructure and this cannot ignore freight. We also explained how a politically viable route to full-scale road pricing - reflecting the type of road, the level of congestion and even the time of day – could start with freight. The road haulage industry already sees road pricing as inevitable—and freight doesn’t vote.

An initial freight-focused road pricing model could serve as a blueprint, balancing fiscal sustainability with environmental goals. But careful design and modelling will be essential to avoid unintended consequences.

Modelling road pricing for freight: the scenarios

MDS Transmodal has developed scenarios for the implementation of road pricing for freight using its Great Britain Freight Model, the “best in class” freight transport demand simulation model. This Road Pricing Scenario assumed that the price per HGV mile was based on internalising all the net external costs. These costs - such as the congestion imposed on other road users, the cost of emissions and the cost of accidents – are encapsulated monetarily in what the UK Department for Transport calls Modal Shift Benefits (MSBs); these are the values per mile that are used by the DfT to justify subsidies to the rail freight industry for the removal of HGVs from the highways network.

Such a system of road pricing would be essentially distance-based, but the price per mile would vary significantly according to the type and location of the road as the prices per mile, as defined by the DfT, were heavily weighted towards the costs of congestion. An HGV on the M25 London Orbital motorway would have to pay a much higher price per mile than the same HGV on the M6 through Cumbria.

The Road Pricing Scenario was then compared with a counterfactual called the Policy Neutral Scenario, where the same aggregate demand for freight was moving between the same origins and destinations within the model, but with the taxation of (diesel) HGVs remaining unchanged.

Modelling road pricing in Great Britain: the results

The results of the modelling suggest that such a system of road pricing would secure some environmental benefits, but there would also be some unintended consequences.

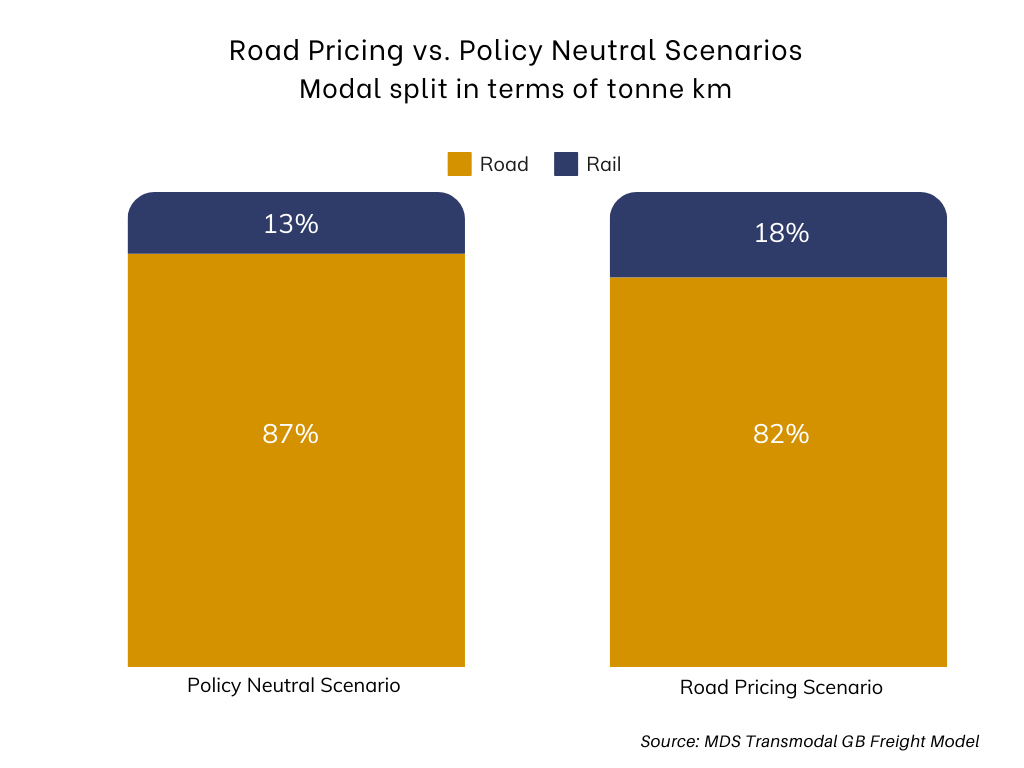

On the positive side, there was a significant shift away from road to rail freight, with an 80% increase in tonne kilometres transported by rail in terms f tonne kilometres. This was partly due to some of the assumptions which favoured rail in any case, such as the availability of additional capacity at rail-connected distribution parks, but was mainly due to road freight being required to pay for its full net external costs. This extent of modal switch is, as it happens, very similar to the Government’s published rail freight target of 75% growth by 2050.

There was also a switch of international road freight through ports away from the shorter ferry routes - principally across the Short Straits between Dover and Calais or Dunkirk - to longer distance RORO routes via the major east coast estuaries; this was due to a proportion of the market choosing to take a longer crossing of the North Sea to avoid congested (and therefore relatively costly) sections of the motorway network in the south of England.

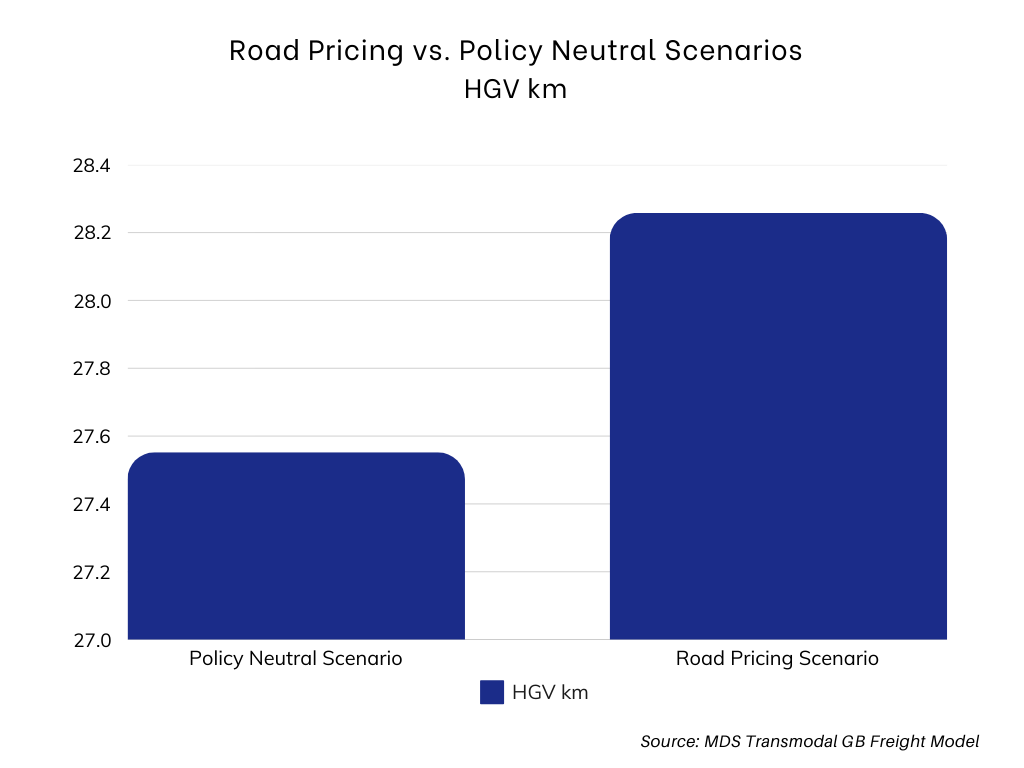

There was also the unintended consequence of a diversion of road freight away from congested roads to less congested sections of the highways network to such an extent that the total road freight tonne kilometres actually increased by 2.5% from 27.6 billion HGV km in the Policy Scenario to 28.3 billion HGV kilometres in the Road Pricing Scenario. This rather perverse result is due to HGVs choosing to divert to longer routes on the highways infrastructure network to minimise door-to-door costs, so that total HGV kilometres increased.

The way forward

The results of the modelling, and lessons from the Maut in Germany, suggest that a system of road pricing for HGVs in Great Britain should be:

- Comprehensive, encompassing the whole highways network to avoid diversion of traffic onto secondary A roads;

- Distance-based, to reflect use of the network;

- Equitable and differentiated, so that it applies to all HGVs operating on the British road network and replaces existing taxation of HGVs with charges per mile that reflect the up-to-date net externalities of each propulsion type and size of vehicle;

- Transparent, with clear charges for the use of different roads by network link and type of vehicle; and

- Signalled well in advance, so that hauliers can plan their investment in new vehicles to minimise their overall capital and operating costs.

While road pricing for HGVs is not seen as a high priority by the Chancellor of the Exchequer at the moment, the logistics industry regards it as inevitable and is likely to accept its introduction if a scheme was designed to incentivise the switch to zero emission vehicles up to 2040 and HGVs were then charged for use of the highways infrastructure network on a comprehensive, consistent and transparent basis over the longer term. As freight doesn’t vote, the introduction of road pricing for freight road could be achieved with relatively little political risk.

Will any of the parties find the political courage to take up the challenge?