Changing lanes: UK box growth lags European neighbours post-Brexit

- By Antonella Teodoro

- •

- 24 Jan, 2023

Of the UK’s 10 largest trading partners only trade with the Netherlands has increased since the UK left the EU

SINCE the UK left the European Union, international containerised trade has been hit by the pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, making it difficult to isolate the consequences of Brexit.

While the volume of cargo traded by the EU last year is estimated to be far above pre-pandemic levels, UK trade is estimated to be lagging its European neighbours.

Although difficult to pin on Brexit, the evidence suggests that since the UK’s separation from the bloc is a marked difference in trade fortunes compared with the continent.

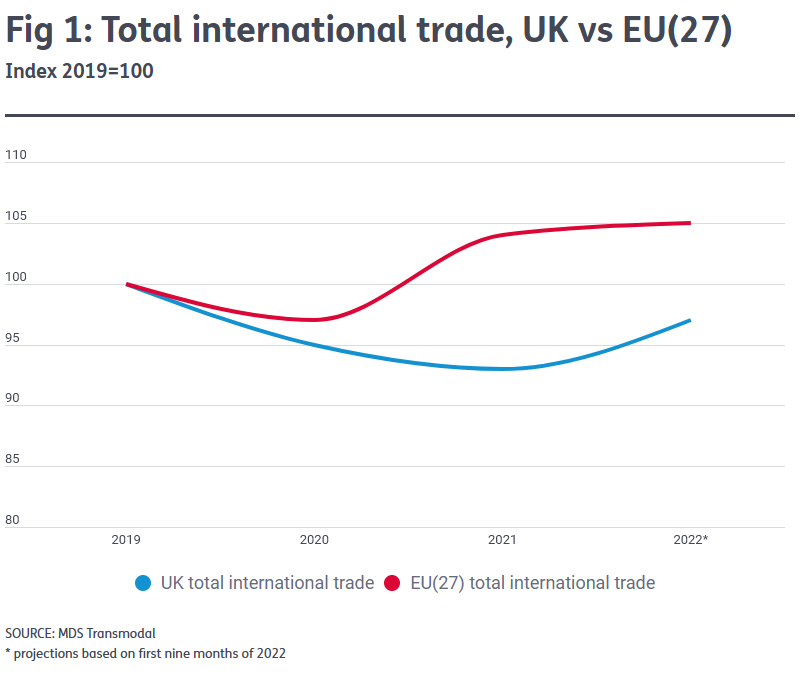

MDS Transmodal’s initial projections for last year (figure 1) suggest an increase of around 4.6% compared with 2019 in overall cargo (measured in teu moved via sea as well as overland) traded to and from the EU. For the UK, a contraction of 3% has been projected over the same period. MDST's figures include all unitisable trade measured in teu.

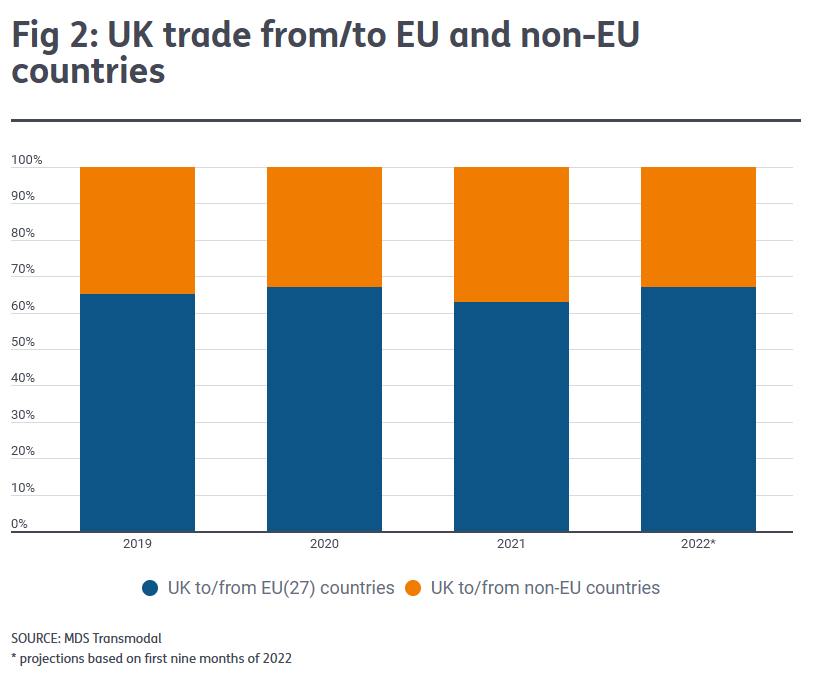

Looking at the proportions of UK trade with EU and non-EU countries, we estimate this has changed only modestly since 2019.

For 2022, MDST projected that the EU accounted for 67% of total international trade for the UK, up from 65% in 2019 (figure 2).

The two percentage points increase estimated for UK trade with the EU is driven by a large contraction in UK trade with non-EU countries rather than an increase in the volume moved between the UK and the EU.

More specifically, while the volume moved in 2022 between the UK and the EU has remained substantially stable compared with 2019, the volume traded between the UK and non-EU countries is estimated to have contracted by around 7.5%.

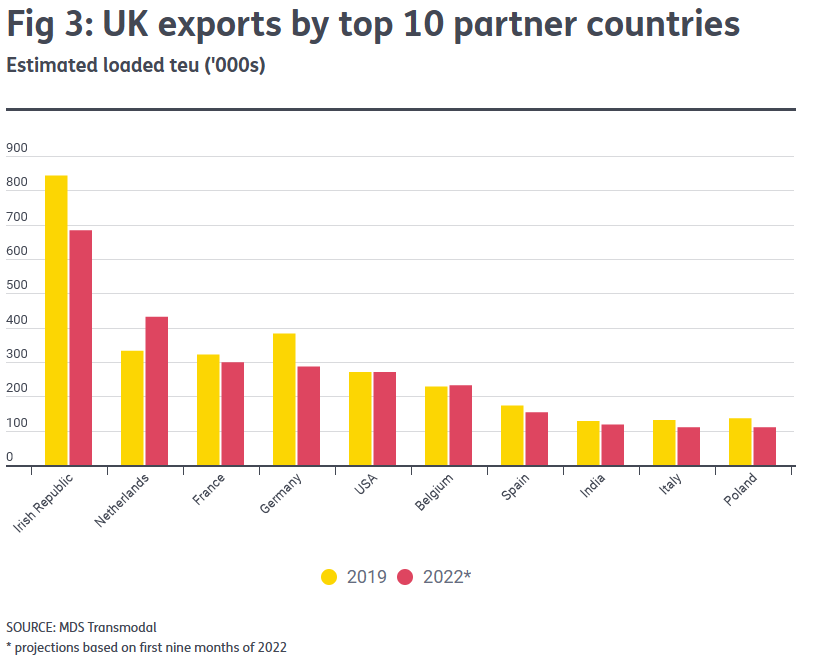

MDST observes that the UK’s key partner countries have remained substantially the same over the past few years, despite a large fluctuation in container volumes shifted both in terms of exports and imports.

For instance, on the export side we estimate a contraction of almost 20% for cargo moved to Ireland and approximately 25% to Germany, while volumes to the Netherlands are estimated to have gone up by around 30% (figure 3).

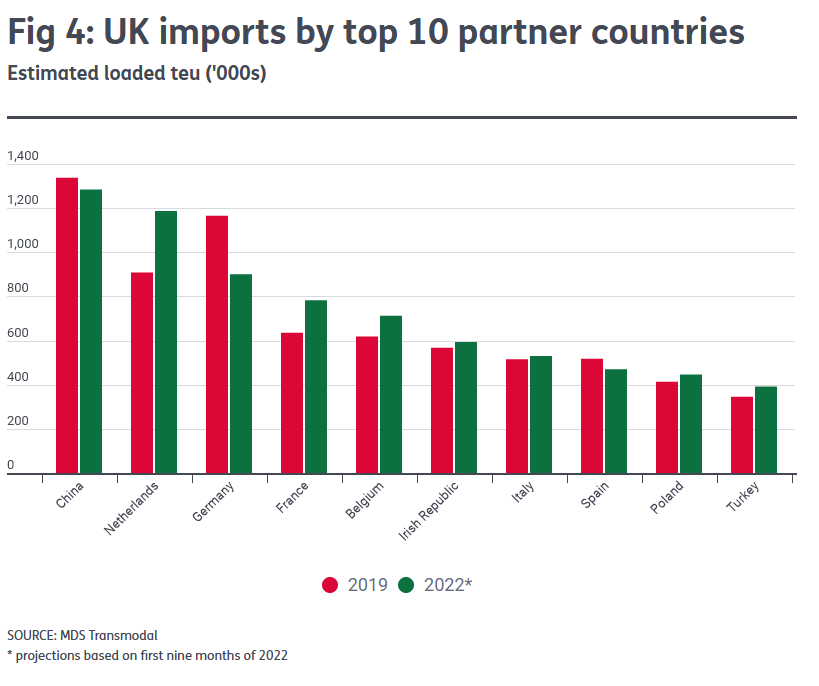

On the import side, China remains the major partner country for the UK, despite an estimated contraction of approximately 4%.

Import volumes from Germany are down by 23%, from Spain by around 9.3%, while for all other countries in the top 10 league we estimate an increase (the Netherlands reports the greatest percentage growth, equating to more than 31%), as shown in figure 4.

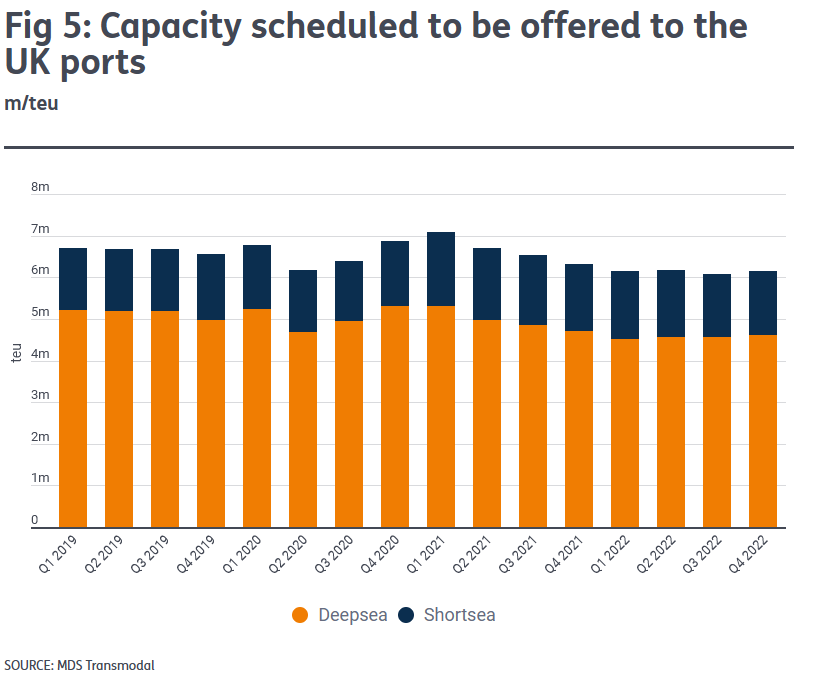

In contrast, the overall capacity offered to EU ports is estimated to have increased by 5% between 2019 and 2022.

An increase driven by the capacity allocated to the deepsea markets, up by circa 9%.

To what extent Brexit is to blame for the different performances observed for the UK compared to the EU countries would require an assessment that goes beyond the comparison of overall trade and supply.

What is clear, however, is international trade in and out of the UK has deteriorated since its breakaway from the EU.